“Here’s What You Get”

An Introduction to Comic Book Paratexts

“Here’s What You Get”:

An Introduction to Comic Book Paratexts

John A. Walsh, Indiana University

When a reader picks up a traditional single-issue floppy comic, a trade paperback collecting multiple issues of a comic that initially appeared in floppy form, or a long-form comic originally published as a hardback book, the reader experiences a wide array of graphic and textual phenomena. Of course, the reader will encounter the expected panels, cartooning, word balloons, and captions that we recognize as comics, or sequential art. But the reader will also find other content in and around those comics — fan mail, advertisements, and publisher news in features such as Marvel’s “Bullpen Bulletins” or DC’s “Direct Currents.” This essay explores “what you get”— what is included and communicated—through the entirety of the comic book document.

In literary studies, the paratext refers to textual and documentary components surrounding or otherwise associated with a text. Paratexts—extensively explored in Gérard Genette’s Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation (1987, 1997)—include titles, dust jackets, intertitles (such as section or chapter titles), prefaces, tables of contents, indices, certain types of notes, epigraphs, publisher reviews, auto-reviews, interviews and conversations with authors and creators, or relevant text from letters and private correspondence.

Paratextual elements provide important personal, authorial, and cultural context and can influence the reception and interpretation of a text.

The table of contents of Genette’s book is a sort of taxonomy of paratexts, with sections devoted to the many different categories of paratexts, such as cover, title page, name of author, titles, dedications, epigraphs, and so on.

In exploring the different types of paratexts, Genette also discusses the function of each particular type. For instance, Genette writes, “[T]he basic function of the original authorial note is to serve as a supplement, sometimes a digression, very rarely a commentary” (p. 327).

While Genette focuses primarily on traditional literary texts, many of his categories translate—sometimes with intriguing variation—into the world of comics.

Comics include many of the types of paratexts that Genette explores in traditional literary texts, but comics also include distinct types — such as peritextual correspondence, or fan mail — that are not present in the same way in the traditional literary texts that concern Genette.

Genette divides the paratext into two general categories, writing, “paratext = peritext + epitext” (p. 5). The first category, peritexts, refers to paratexts that exist within the same physical volume (or the same floppy comic book):

Within the same volume are elements such as the title or the preface and sometimes elements inserted into the interstices of the text, such as chapter titles or certain notes (Genette, pp. 4-5).

The second category, epitexts, identifies those paratexts that exist outside the physical volume (or floppy comic):

[A]ll those messages that, at least originally, are located outside the book, generally with the backing of the media (interviews, conversations), or under cover of private communication (letters, diaries, and others) (Genette, p. 5)

Some comparative examples from traditional literary texts and comics will help illustrate these concepts.

Peritexts

Covers

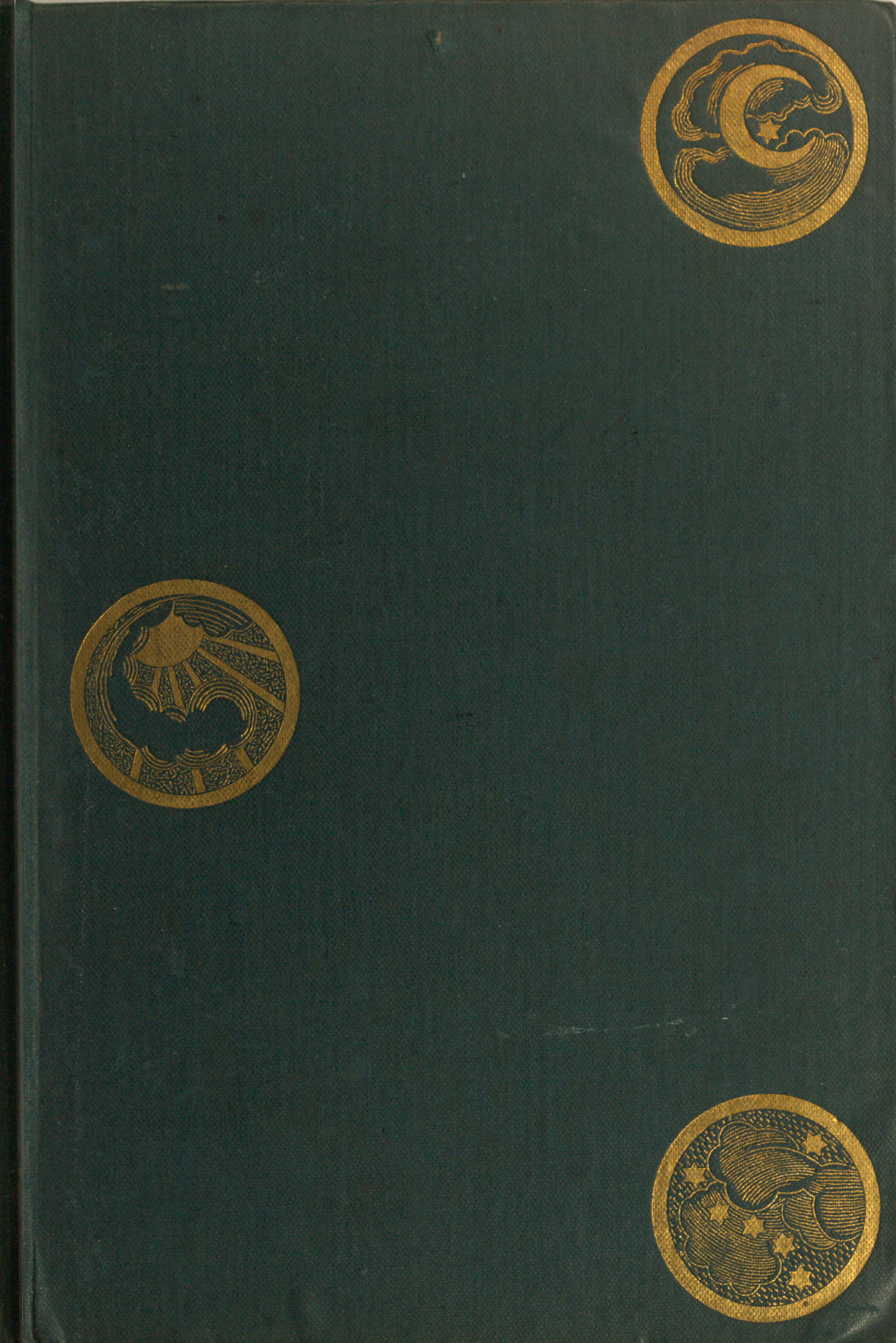

In 1871, Victorian poet Algernon Charles Swinburne published Songs Before Sunrise, a collection of poems, including many political poems supporting Italy’s 19th-century struggles for independence. The cover—a paratext of Songs Before Sunrise—was designed by Swinburne’s close friend, poet and artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Rossetti was a Italian-British poet and artist and a leading member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, an influential group of young, rebellious artists. The cover design by Rossetti acknowledges and emphasizes Swinburne’s personal friendship with Rossetti and his affiliation with the Pre-Raphaelite artists and poets. The paratext is evidence of these relationships.

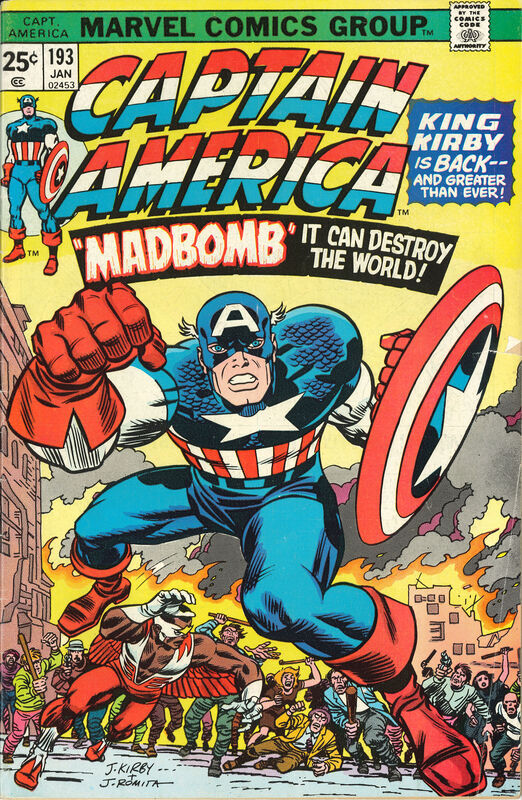

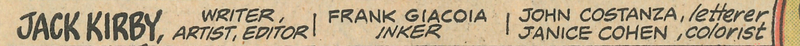

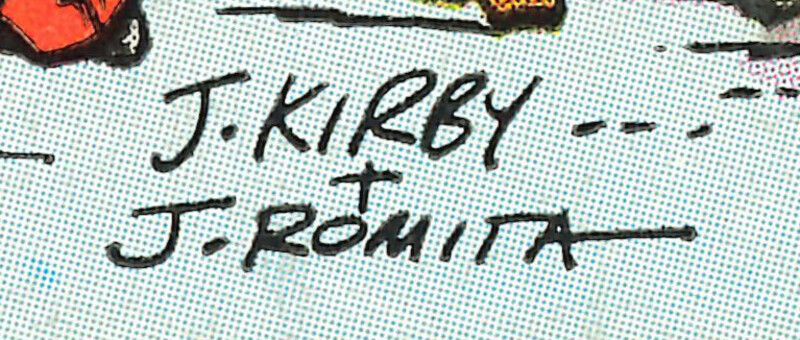

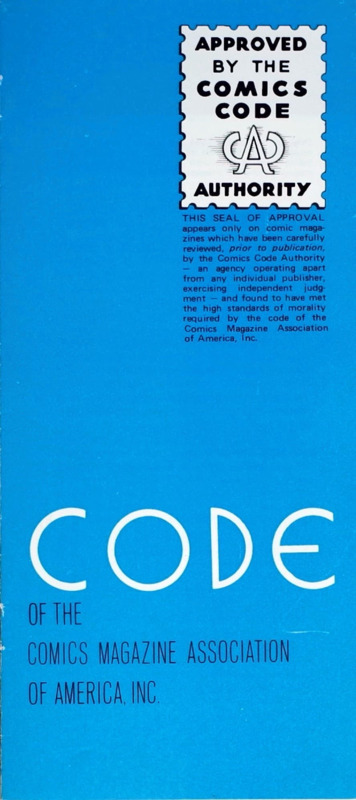

A cover from a 1970s Marvel comic book explicitly and implicitly provides a wealth of information. The cover below includes the series title: “Captain America”; a story title: “‘Madbomb’: It Can Destroy the World!”; bibliographic information, such as publisher (“Marvel Comics Group”) and issue number (“193 JAN”); the price: “25¢”; a content advisory: “Approved by the Comics Code Authority”; artists’ names: “J. Kirby + J. Romita”, and a publisher’s announcement on the return of longtime Marvel artist Jack Kirby: “King Kirby is back – and greater than ever!”. From 1971-1975, Kirby left Marvel to work for rival DC Comics, and his departure and return are two highlights in a complex tale of the industry’s mistreatment of an unacknowledged genius of the art form.

This cover also includes information on creators not found elsewhere in the document. For instance, the formal credits on the interior splash page omit John Romita, who inked Jack Kirby’s pencils for the comics’s cover. The cover itself, however, includes both artists’ names: “J. Kirby + J. Romita.”

The rather inconspicuous seal of the Comics Code Authority, found on the covers of American comics from 1955 into the early 21st century, signals the fraught history of the 1950s anti-comics campaigns championed by psychologist Frederic Wertham.

Thus, a “simple” comic book cover both provides important bibliographic and commercial details and gestures towards the complex narratives of Kirby’s life and career and the battles that led to the creation of the Comics Code Authority.

Title pages

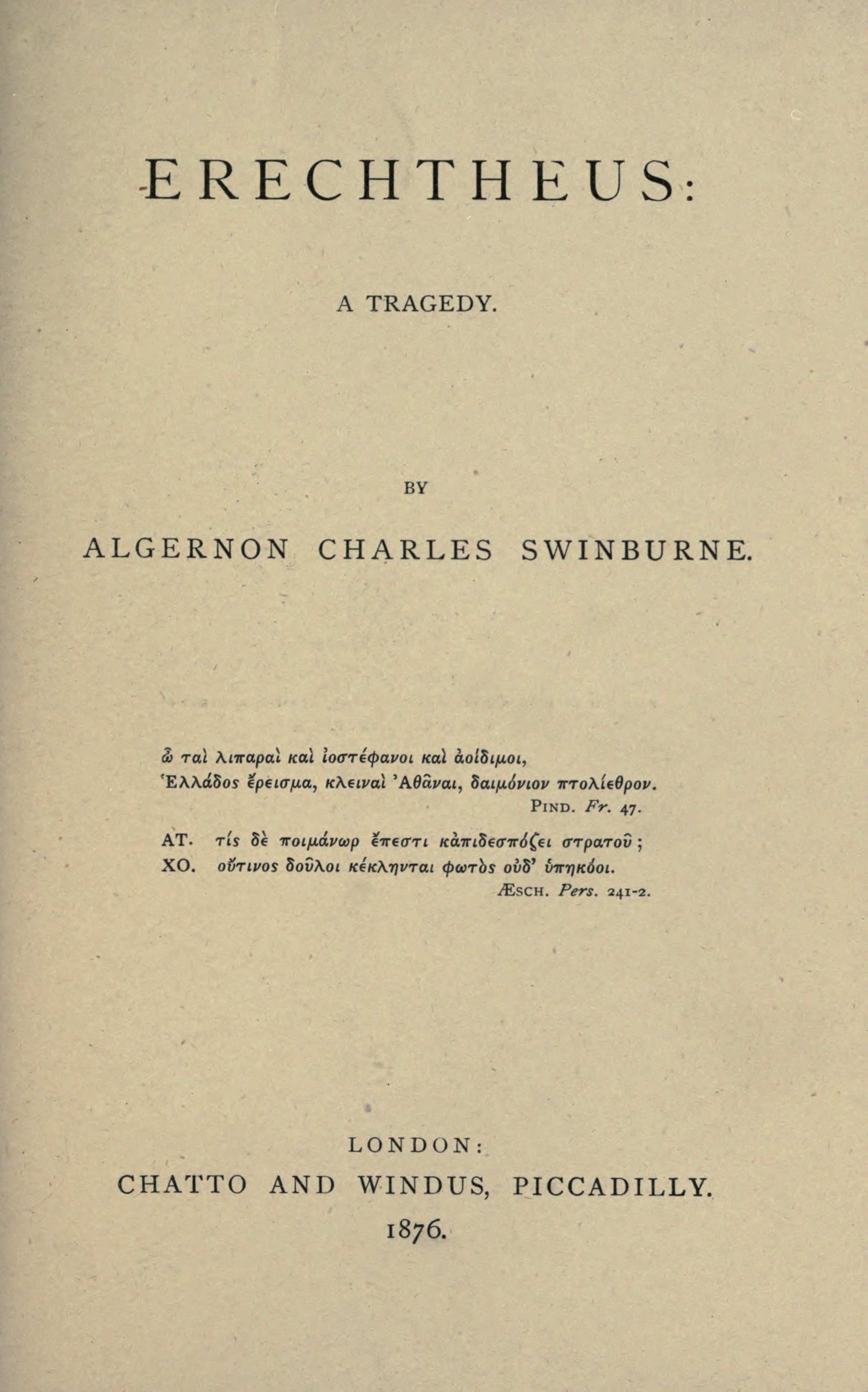

The interior title page for a 19th-century book of poetry contains a great deal of information. The example below, from Swinburne’s Erechtheus (1876), includes the title of the work, the name of the author, two epigraphs — quotations from Pindar and Aeschylus, the place of Publication, the publisher, and the date of publication.

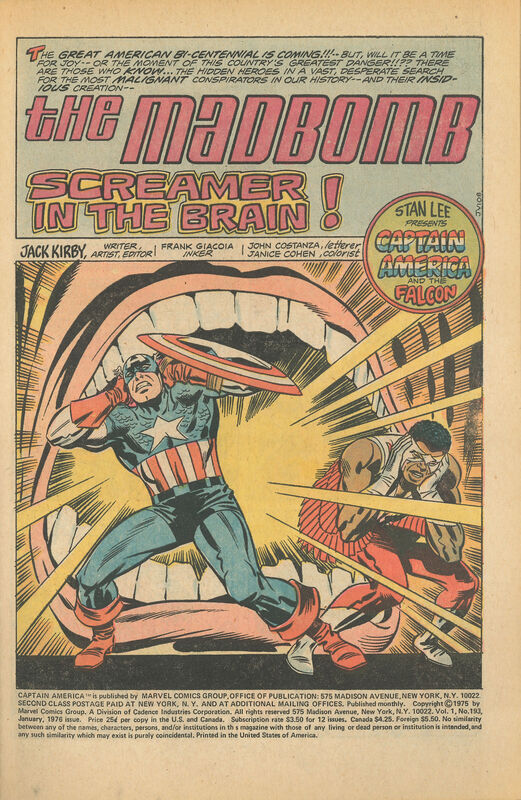

The interior splash page in a comic is in many ways analogous to the title page of a traditional literary work. The interior splash page, a standard feature of many mainstream commercial comics, repeats information and partexts found on the cover, such as the publisher, the name of the creators, and the story title.

However, commonly, the interior story title is a variant of the title found on the cover. For example, the interior title below reads “The Madbomb Screamer in the Brain!” while the cover (above) for the same comic reads, “‘Madbomb’ It Can Destroy the World!” he result is two paratextual titles competing with, commenting on, and amplifying one another.

The indicia, also typically found on the interior splash page, includes important bibliographic information include the publisher, publisher location and address, volume and issue number, date, and legal disclaimers.

Genette’s paratext categories include “intertitles,” or interior titles such as chapter and section titles, and we find many examples of these in comics.

Dedications

Dedications are another type of paratext discussed by Genette and a common feature of traditional literary texts. Again we draw examples from Swinburne. In the first case we see the dedication to the painter Edward Burne Jones, a close friend of Swinburne. The dedication is from Swinburne’s most famous volume, Poems and Ballads (1866). A second example is an implied dedication to one of Swinburne’s literary heroes, Victor Hugo, on the occasion of Hugo’s 78th birthday.

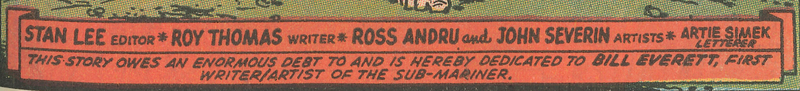

While they are not as frequent as in non-graphic literary texts such as novels, plays, and volumes of poetry, dedications are also present in comics books. As in the three examples below, comic book dedications often indicate a debt of gratitude to comics creators from an earlier generation. In the first example, writer Roy Thomas dedications a Sub-Mariner story from Sub-Mariner #32 (June 1971) to Bill Everett, who in 1939 created the Sub-Mariner character. Everett passed away less than two years after the publication of this dedication, in February 1973, at the age of 55.

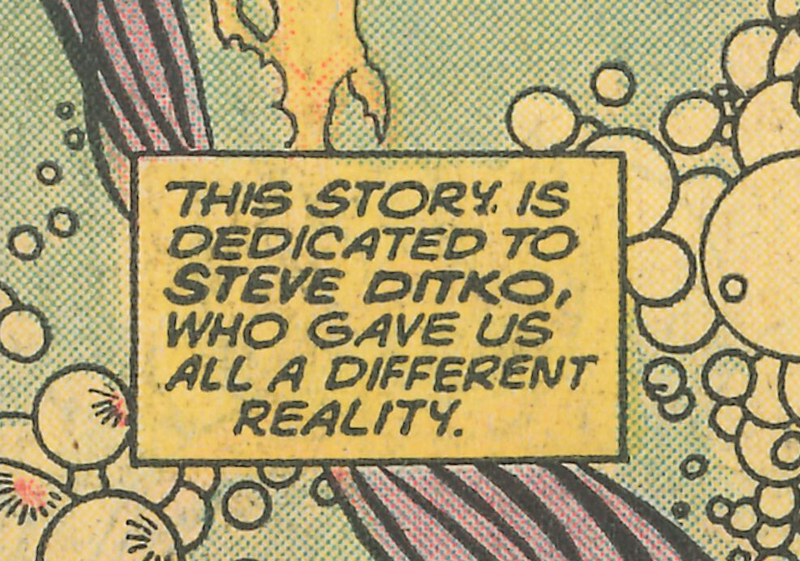

Another example is writer/artist Jim Starlin’s dedication to artist Steve Ditko in a story featuring the character Adam Warlock, from Strange Tales #181 (August 1975), to artist Steve Ditko. The entire page is a visual dedication implied by Starlin positioning Adam Warlock within a psychedelic dreamscape that echoes similar dreamscapes introduced by Ditko in his work on Marvel’s Doctor Strange, who first appeared in the same title in Strange Tales #110 (July 1963). But there is also an explicit paratextual dedication: “This story is dedicated to Steve Ditko, who gave us all a different reality.”

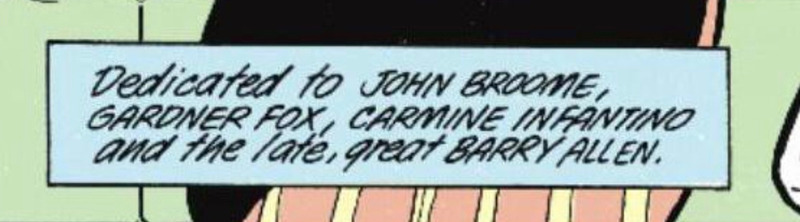

Grant Morrison’s dedication in Animal Man #8 (February 1989) bucks convention by including fictional character Barry Allen among comics creators John Broome, Gardner Fox, and Carmine Infantino.

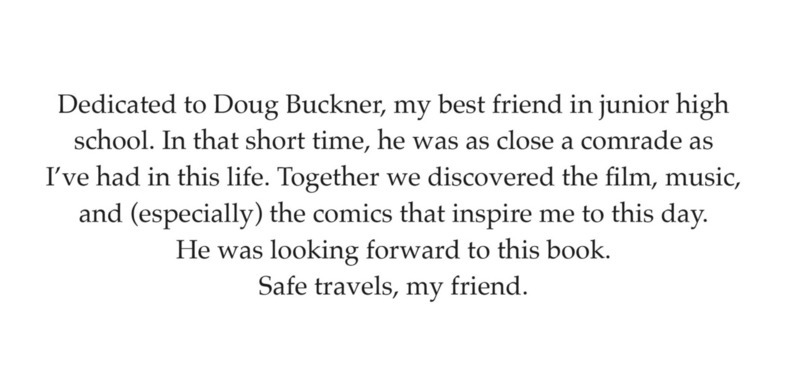

Derf Backderf’s dedication to his friend Doug Buckner appears in his hardbound book-length documentary comic Kent State: Four Dead in Ohio (2020). Suggesting the influence of physical format on the book’s contents, this dedication, appearing in a hardbound book, more closely resembles, visually and rhetorically, a formal dedication found in a traditional literary work than the examples above of in-panel dedications found in “floppy” comic books.

Epigraphs

Epigraphs, which are short quotations, often with a bibliographic citation for the source of the quotation, at the beginning of a book, chapter, or poem. Like dedications to literary and artistic figures, epigraphs can suggest creative debt or influence. They also designate a specific intertextual relationship between the quoted text and the work in which the epigraph appears. There are at least three agents involved in an epigraph, as described by Genette:

[T]he attribution of the quotation raises two theoretically distinct questions, although neither is as simple as it appears to be: Who is the author, real or putative, of the text quoted? Who chooses and proposes that quotation? I will call the author the epigraphed; and the person who chooses or proposes, I will call the epigrapher, or sender of the epigraph (its addressee — no doubt the reader of the text - being, if you insist, the epigraphee). (pp. 150-151)

Genette goes on to identify four functions of an epigraph.

- “elucidating and thereby justifying not the text but the title” (p. 156);

- “commenting on the text” (p. 157);

- implicitly dedicating the work to the individual quoted (p. 159);

- marking, by an epigraph’s presence or absence, “the period, the genre, or the tenor” of a piece of writing (p. 160).

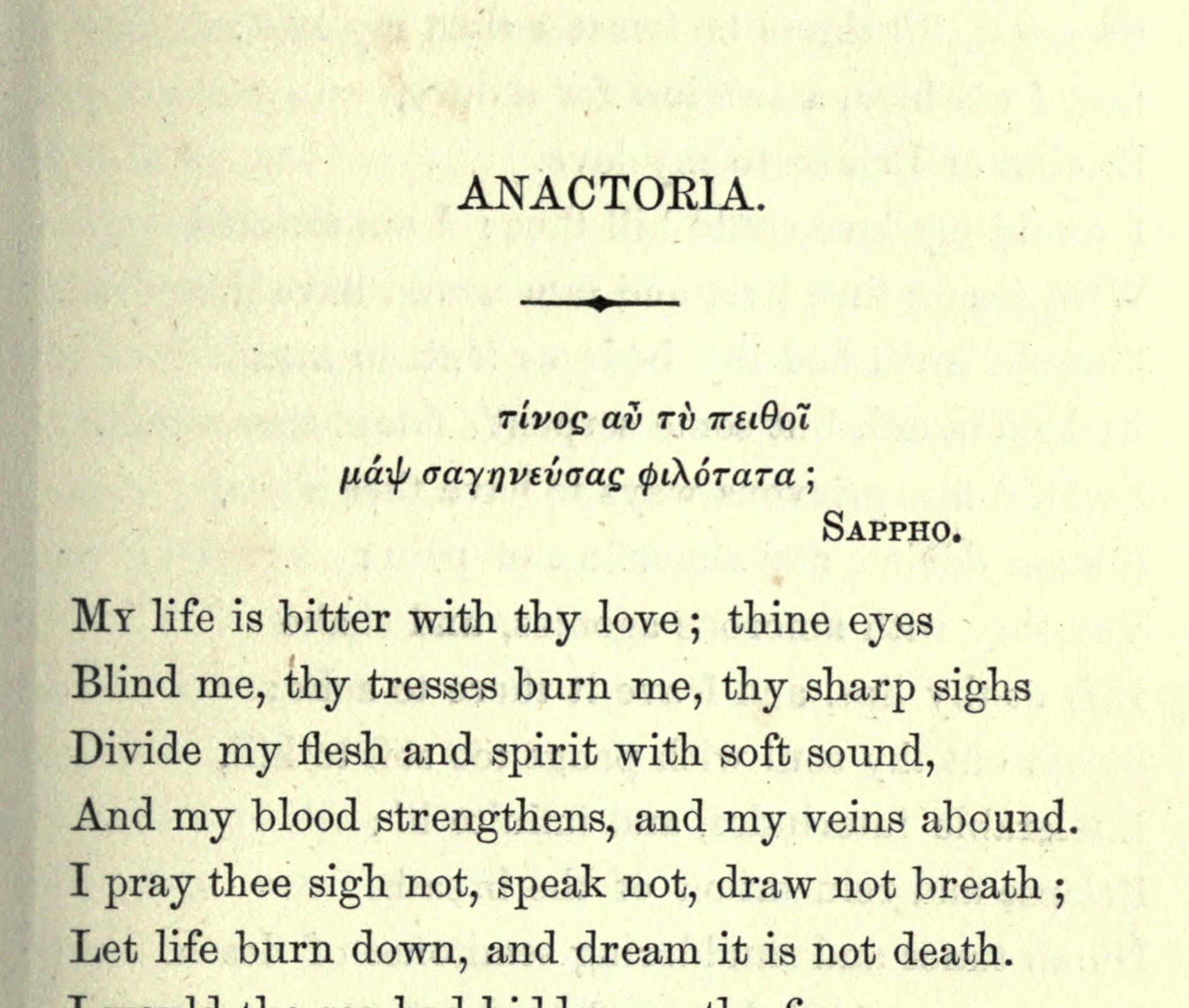

Below is another nineteenth-century example from Swinburne. At the head of his poem “Anactoria” from his 1866 volume Poems and Ballads, Swinburne quotes the Greek poet Sappho. “Anactoria” is a dramatic monologue in which the speaker, Sappho, addresses her lover, Anactoria.

τίνος αὖ τὺ πειθοῖ

μὰψ σαγηνεύσασ φιλότατα ;

Sappho.

The epigraph to Swinburne’s “Anactoria” accomplishes all the functions set by Genette. The poem is a tortured and passionate address by Sappho, and the identification of Sappho in the epigraph elucidates, amplifies, and justifies the poem’s title. Haynes notes, “The epigraph is an emendation, perhaps Swinburne’s own, of a corrupt line in [Sappho’s] Aphrodite Ode; Swinburne’s version means, ‘Whose love have you caught in vain by persuasion?’” (p. 333). In the Aphrodite Ode, the speaker calls upon the goddess Aphrodite for aid in the pursuit of an unnamed lover. Thus, both Swinburne’s poem and Sappho’s amplify one another.

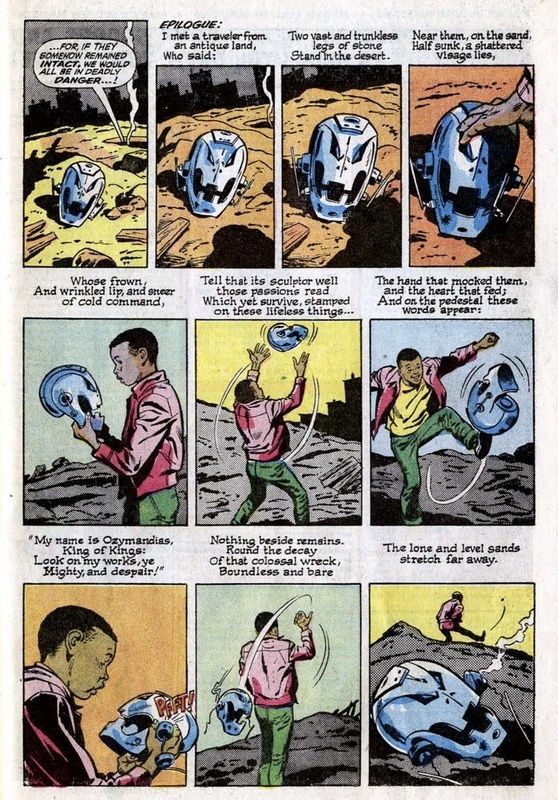

Among Swinburne’s many literary heroes is the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. We find an excellent example of a comic book epigraph in Roy Thomas’s use of Shelley’s sonnet “Ozymandias” (1818) in Avengers #57 (October 1968).

Below is the full text of Shelley’s poem:

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desart. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

“My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

No thing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Publisher’s paratext: advertisements, editorials, and news

Advertisements

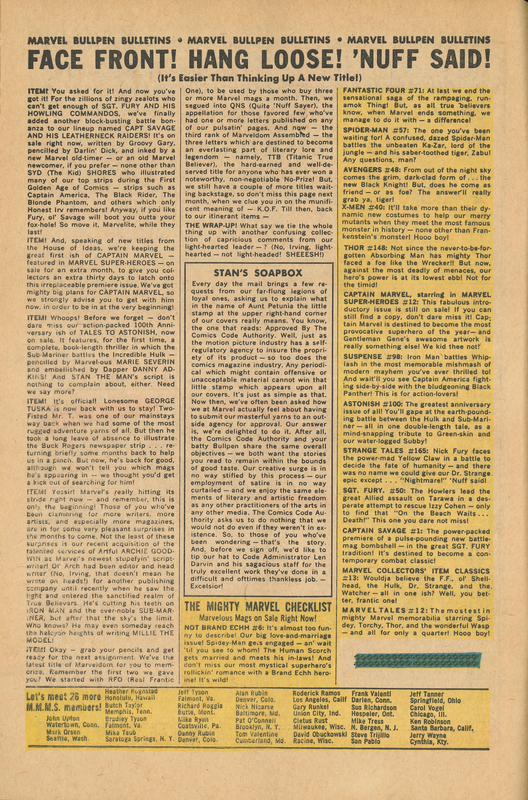

The paratexts of comics will also include lists of available works by the comics publishers. Two examples below, a “Mighty Marvel Checklist” from Marvel’s “Bullpen Bulletins” from January 1968 and an advertisement for subscriptions to Marvel comics and comics magazines, include such lists.

The second example above, the advertisement for subscriptions Fantastic Four #162 (September 1975), illustrates the value of paratexts for the study of comics and comics publishing history. The advertisement includes an option to subscribe to the title Scarecrow. While the character appeared in single issues of three different titles around this time — Dead of Night #11 (August 1975), Marvel Spotlight #26 (February 1976), and Marvel Two-in-One #18 (August 1976) — a serial comic titled Scarecrow was never published by Marvel. This advertisement suggests such a titled was planned but then abandoned.

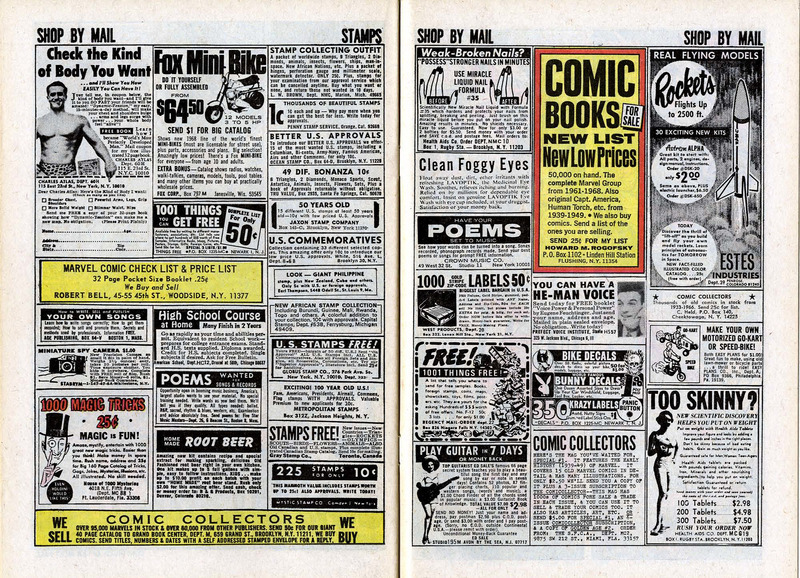

For many mainstream American comic books, advertisements are by far the most common type of paratext. A single page of a silver or bronze-age comic could contain a dozen or more small advertisements.

The single double-page spread below includes 37 separate advertisements. The size and density of the ads is reminiscent of classified advertisements found in newspapers.

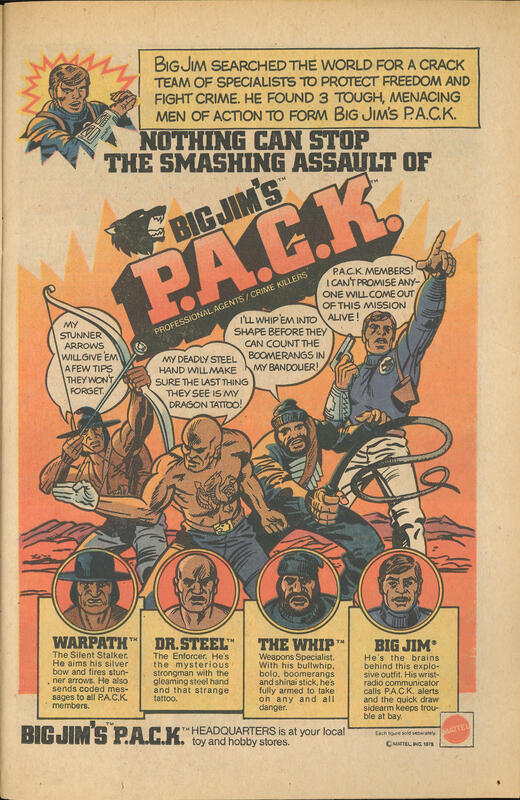

Many comic book advertisements co-opt formal elements from comics. For example, the advertisement below for “Big Jim’s P.A.C.K.” action figures This advertisement for Big Jim’s P.A.C.K. action figures incorporates comics-styled illustration, lettering and typography, captions, and word balloons.

A 1968 advertisement for International Correspondence Schools (ICS) completely abandons traditional ad copy, format, and structure, instead employing the comics format to tell the fictional story of a high school dropout who becomes a success by using the advertised product.

Those interested in topics such as gender roles in comics will find much of interest in comics advertisements. The advertisement below is recruiting comic book readers to sell Grit newspaper in their neighborhood. The recruiting message is addressed to “Fellows” and continues “If you’re a boy 12 years old or older, you can be a happy, prosperous GRIT salesman.” The mail-in form asks, “Are you a boy?”

Later versions of this advertisement would replace “Look, Fellows!” with “Look, Friends!” and “Are You a Boy?” with “Male or Female?”

Correspondence

Notes

Genette defines a note as follows: “A note is a statement of variable length (one word is enough) connected to a more or less definite segment of text and either placed opposite or keyed to this segment” (p. 319). Genette also distinguishes between “between notes connected with texts that are themselves discursive (history, essays, and so forth) and notes - as a matter of fact, far less common - that adorn or mar, as you like, works of narrative or dramatic fiction or lyric poetry” (p. 325). We find both kinds of notes in comics.

However, most comic books are not “discursive” documents. They are works of fiction. And many are serial works of fiction. Many of the notes in serial comics function to educate the reader about the long serial continuity of comics, the expansive fictional universes in which many comics take place. They explain events that occur in previous issues of the serial publicaton or in separate publications from the same publisher and fictional world or universe.

A distinctive type of note found mostly in comics from the genre of “teen humor fashion comics” (Walsh 2021). In these teen humor fashion comics, like the Katy Keene comics from Archie comics or the Millie the Model comics from Marvel, the comics creators solicited fashion designs and other contributions from readers. Readers whose designs and ideas were used in the comics were credited in notes.

Documentary partexts

Genette does not devote a full chapter or section of his seminal book to “documentary” paratexts; however, in his conclusion he writes, “[T]his inventory of paratextual elements remains incomplete … For instance, certain elements of the documentary paratext that are characteristic of didactic works are sometimes appended, with or without playful intent, to works of fiction” (p. 404). He goes on to list a number of examples:

Senancour’s Oberman includes a sort of thematic index called “Indications,” arranged in alphabetical order (Adversité, Aisance, Amitié [Adversity, Ease, Friendship] …); Moby-Dick opens with a comprehensive documentary dossier about whales; Updike’s Bech: A Book ends with an imaginary bibliography of works by and studies about the hero (the studies are attributed apocryphally to real critics); the “appendix” of Perec’s Vie mode d’emploi [Life: A User’s Manual] contains a floor plan of the building, an index of persons and places, a chronology, a list of authors quoted, and an “Alphabetical Checklist of Some of the Stories Narrated in this Manual.” Novelistic works like Zola’s Rougon-Macquart, Thackeray’s Henry Esmond, Nabokov’s Ada, or Renaud Camus’s Roman roi contain family trees constructed by the authors themselves. For the Portable Faulkner of 1946, Faulkner drew a map of Yoknapatawpha County; and Umberto Eco drew a plan of the abbey in The Name of the Rose. (pp. 404-405)

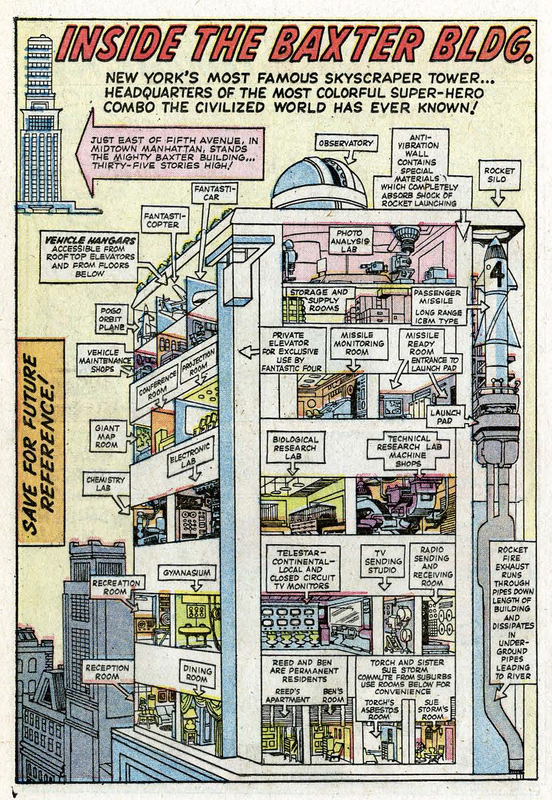

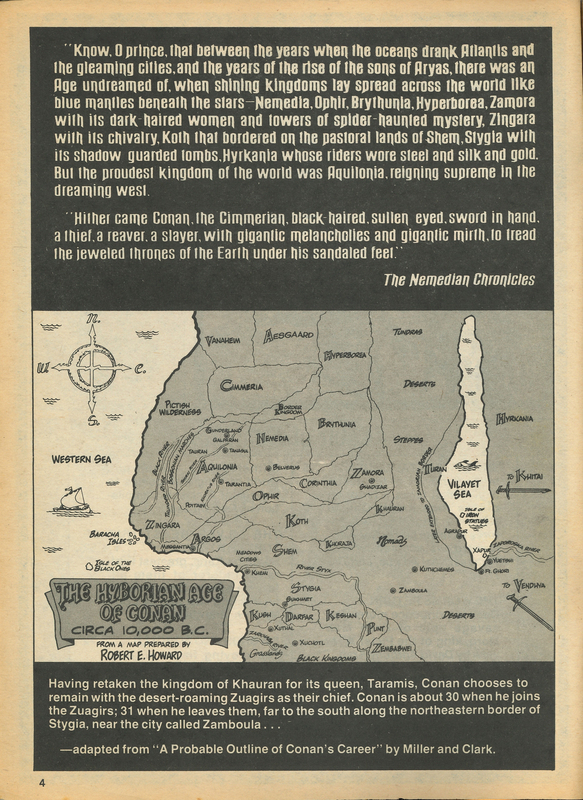

Documentary paratexts are not uncommon in comics, and they are of particular interests because, like epigraphs and notes, they are generally created by the creators (writers and artists) of the main comics narrative, and they are conceptually closer to the “text” than many other comic book paratexts, like fan correspondence and advertisements. For instance, a sectional view of the Baxter Building, headquarters of Marvel’s Fantastic Four superhero team, provides spatial contexts to narratives about the Fantastic Four. These sectional views are intended as persistent reference material for readers. An example by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby from 1963 implores readers to “Save for future reference!” Another, by Marv Wolfman and Kieth Pollard, from 1968 announces itself as a “handy-dandy reference.” Similarly, a map of the “Hyperborian Age of Conan” adds spatial contexts to stories about Robert E. Howards fictional world and its inhabitants.

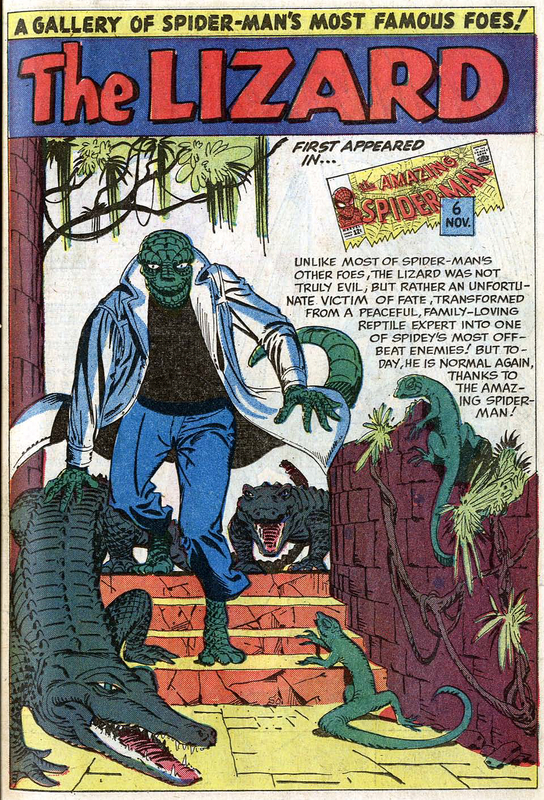

Less narrative-focused documentary paratexts include “pin-up” pages of popular characters, often with explanatory text and bibliographic details about notable appearances of the character. Like the sectional views of the Fantastic Four’s Baxter building, these pin-ups also serve as reference material, with a short biography of the featured character and bibliographic information about the character’s first appearance.

Epitexts

Victorian poet Algernon Charles Swinburne, authored a number of important epitexts that illuminate his poetry and contextualize within English poetry and the larger canon of Western literature. In his edition of three of Swinburne’s epitexts, Clyde Kenneth Hyder writes that these “systematic replies to [Swinburne’s] critics” contained “imaginative interpretations of their author’s own poems or acute criticism of other poets, as well as stimulating observations on poetry in general” (p. vii).

In “Notes on Poems and Reviews” (1866), Swinburne is responding to attacks upon his recently published volume Poems and Ballads (1866). “Notes” is a mechanism, and epitext outside the physical and conceptual confines of the Poems and Ballads volume, by which Swinburne can respond to his critics and speak to his readers, his fellow poets, and the larger literary world about his poetry. Similarly, comic book creators use epitextual mechanisms for such communications. These epitexts may be found in comics-related books, newspapers, magazines, and fanzines, on radio and television, and in audio and video recordings of panels and interviews at comic book conventions and similar events.

Conclusion

21st-century comics fans, readers, and scholars have access to tens of thousands of print and digital collections and reprints of comics from throughout comics history. However, in most cases those reprints are woefully incomplete and inadequate for serious scholarship. They all too frequently lack the crucial original paratexts — the fan mail, advertisements, publisher news, and more – that are an integral part of the comic book document and are in conversation with the core comic book text, its audience, its traditions, and its history. In his investigation of documentary comics, Schmid (2021) writes, “While the prefix “para-” suggests a hierarchy between such “marginal” texts and the narrative discourse, the paratext is a constitutive element of the documentary graphic narrative book and necessitates investigative attention. Instead of being a frame that contains the story within, the various paratexts are active components of documentary comics’ work of framing” (p. 65). Of course, this claim for the constitutive nature of the comic book paratext applies to all comics, not just those we might classify as documentary. In most contexts, our understanding of comics is enriched by giving careful investigative attention to the comic book paratext.

Works Cited

Genette, G. (1997). Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation (J. E. Lewin, Trans.). Cambridge UP. Haynes, K. (2000). Poems and Ballads & Atalanta in Calydon (A. C. Swinburne). Penguin UK. Hyder, C. K. (1966). Preface. In Swinburne Replies: Notes on Poems and Reviews, Under the Microscope, Dedicatory Epistle. Syracuse University Press. Shelley, P. B. (1819). Ozymandias. In Rosalind and Helen, a modern eclogue; with other poems. C. and J. Ollier. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/dul1.ark:/13960/t1bk2mq33 Schmid, J. C. P. (2021). Frames and Framing in Documentary Comics. Palgrave Macmillan. Walsh, J. A. (2022). “It Was as Much Ours …”: Reader Contributions to Teen Humor Fashion Comics. Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society, 6(2), 142–171. https://doi.org/10.1353/ink.2022.0011